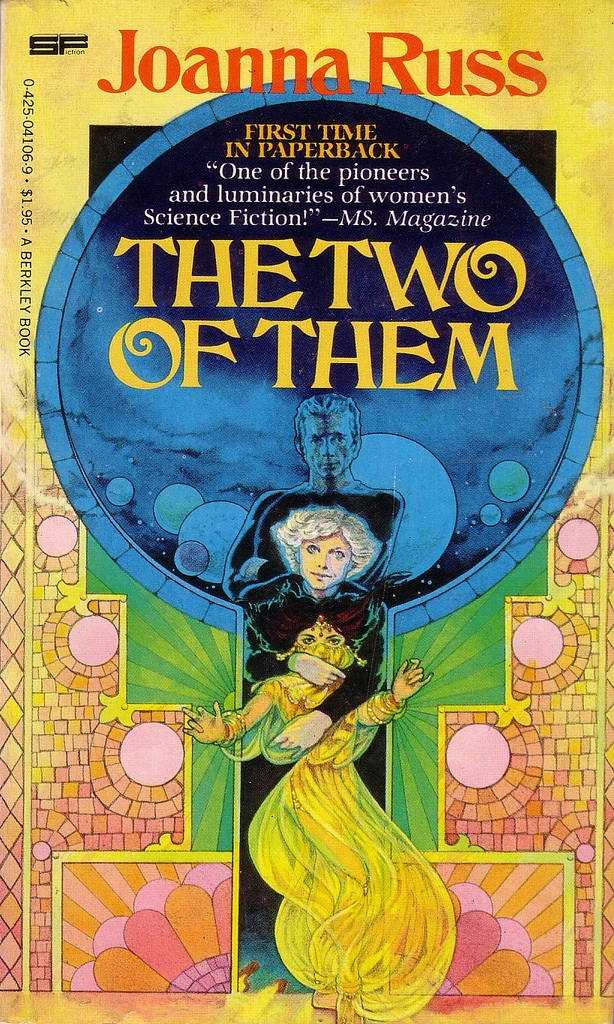

Russ’s next book, following We Who Are About To , is a short novel titled The Two of Them. It is her second-to-last novel and last SF novel; the next two pieces of fiction she will write are a children’s book and a mainstream lesbian novel. Berkley first published the book in 1978, and it is currently in print from Wesleyan University Press in their “modern science fiction masterpiece” series, much like We Who Are About To

The Two of Them follows two agents of the Trans Temp agency (which appears in shadow in The Adventures of Alyx also, during Picnic on Paradise and “The Second Inquisition”), Irene and Ernst, to a small space settlement, Ka’abah, that uses a truncated and rearranged form of Islam as their guiding policy. Irene was relocated from her universe and time by Ernst as a teenager, and now she goes about committing strange espionage and occasionally rescuing other girls and women from their trapped lives. Things begin to fall apart as Irene realizes that Trans Temp is no different from her world, nowhere is truly free or safe, and Ernst is as much her enemy as he has ever been her ally. She realizes she’s a token woman in the agency. The trap is closing again, and she can’t take it anymore.

To come so far. Like Elf Hill. And all for nothing. To spend your adolescence dreaming of the days when you’d be strong and famous. To make such a big loop—even into the stars—and all for nothing.

She thinks: What a treadmill. (117)

The Two of Them strikes me as a prolonged howl of anguish in the form of a novel. It’s a messy book, not in its prose, which is flawless as ever for Russ, but in its relationships and its arguments, its breaking of the fourth wall and the rules of narrative to make a point. The Two of Them careens back and forth between the chance for change and the impossibility of change, between “the problem with no name” and the freedom a woman might dream of, between love and hate, between anger and helplessness. It ends without “ending,” in a flight to metaphoric imagery that speaks to the thematic argument of the piece without engaging the plot. There is no ending for the reader who desperately wants to know what becomes of Irene and Zubeydeh in the literal sense—there is only the thematic end and the imagery Russ closes on.

I find it interesting that this book is Russ’s last novel-length work of SF—as if she has said all she could say in the form, and the form itself has degenerated into a textual trap. There are no chapter divisions in The Two of Them; it’s a relentless march from the first page until the moment the narrative breaks down, when Russ intentionally shatters the suspension of disbelief to begin speaking directly to the reader. “I made that part up,” she says. She begins telling flights of fancy that would have made happier endings, and then yanks them away. “Well, no, not really,” she says after explaining that maybe Ernst survived his shooting. It’s a difficult trick to work at the end of a story that has otherwise immersed the reader in the reality of Irene and Ernst, reducing them back to characters on a page who Russ puppets at will, without alienating the reader at the same time. She’s not entirely successful on that score; the reaction I have to the same text differs from reading to reading. At times it seems brilliantly heartbreaking, a perfect climax, and at others it seems like a chaotic breakdown, an unwillingness to continue writing in a form that no longer works for Russ as an author. Both are possible, and both have the ring of truth. It’s a maddening text—maddening for the reader, maddening for the author, maddening for the characters.

“The gentlemen always think the ladies have gone mad,” after all, a phrase that becomes the central idea of the finale of the novel—that no matter the reasons behind their actions, or how obvious it seems to the women themselves who are trapped and bound into roles that have no meaning for them, or how simple it would be for the men to simply listen, they won’t. The implication is that they never will. “The gentlemen always think the ladies have gone mad,” remember. Hope for the future in this mode is dismal.

The only hope that remains in the entire text is in the final flight of metaphor, imagined to be Dunya’s barren soul, where Irene and Zubeydeh become another pair, another “two of them,” this time formed of women. It is an empty place, a boneyard, where there is nothing living, not even words with which to discuss the death of her soul. (Again, a cast back to “the problem with no name” that afflicted Irene’s mother Rose, the housewife, who Irene never wanted to become. It is a problem of having no words with which to speak of the agony.) The final lines are surprisingly uplifting, compared to all that came before:

Something is coming out of nothing. For the first time, something will be created out of nothing. There is not a drop of water, not a blade of grass, not a single word.

But they move.

And they rise.

Those lines—of triumphing, in some way, despite it all—are the last word on the subject. I’m not sure that their hope outweighs the terror, the failure, and the hopelessness of the rest of the novel, though. Irene’s life is an endless series of attempts to be free that result in not only failure but an illusion of success that fools even her for some while. Her story is the story of many women—she becomes her ideal self, “the woman, Irene Adler” (Irene loves Sherlock Holmes as a young woman), as part of the Trans Temp agency, and for awhile believes that this means things are getting better, that equality might even be possible. She falls prey to the myth of the singular special woman, which Russ takes apart in her nonfiction some years down the road.

Then, after rescuing Zubeydeh and considering what will happen to her back at the Center—probably she’ll become a nameless, faceless nurse or typist or clerk—Irene has a flash of insight: she’s the only one. And the ease with which Ernst takes away her identities and intends to send her back to be caged again—which the Trans Temp folks could use as an excuse to never have another female agent—drives the point home. She’s not unique. She’s not free. She’s just in a different-looking cage, designed to make her feel as if there’s some chance because she’s not stuck as a nurse or housewife. But, she’s still stuck.

Realizing that is what finally drives her over the edge into a set of decisions that take her radically outside her previous frame of experience. She kills Ernst when he tries to subdue her to take her back to the agency to be caged and “treated” for her “madness” (which is anger at the fact that it seems that women everywhere, in every time and world they go to, are subjugated, and Ernst thinks that must just be the way of things). She kills him not because she’s that angry at him, or because she feels betrayed by him. “Sick of the contest of strength and skill, she shoots him.”

She’s tired of all the bullshit. It’s easy to understand.

However, while I understand the arguments and the anguish in the text, The Two of Them is a book that I can’t make my mind up about. I’m not certain judging by the text that Russ could, either. Irene is in many ways unsympathetic—she’s brash, she’s cruel, she’s full of vitriol and mockery for the world around her. However, her plight and the plight of women everywhere in patriarchy that Russ is using her to illustrate are deeply sympathetic, at least for a reader versed in feminist theory. The breakdown of the text at the end, as if to comment that the form of the SF novel was no longer functional for Russ in a meaningful way, lends itself to my uncertainty about a final reaction to the book.

The Two of Them, like most of Russ’s novels, is brutal and awful and relentlessly upsetting. The characters—Irene the “madwoman,” driven there by circumstance and necessity, Ernst the idiot, stuck in his ways and not deserving of his eventual death, Zubeydeh the histrionic child, uprooted from her home but an astonishingly cruel little monster of a girl, and her family worst of all—are supremely unpleasant. The book has things to say about feminism, women’s roles in the universe, and the traps women find themselves in, but then breaks down at the end in its attempt to make its final arguments. (Arguments that Russ will later make with excellent clarity of vision in nonfiction, the form she turns to after writing her final novel.)

It’s not fair to say “I liked it” or “I didn’t like it.” I couldn’t answer honestly even if I thought it was fair. The Two of Them isn’t reducible to a mild, simple aesthetic judgment. Is it worthwhile? Yes. Is it an important part of Russ’s oeuvre? Yes. Would I read it again? I’m not sure. It’s also strangely dismissive of queer sexuality, women’s and men’s, and makes snide asides at how culture views men’s erotic attachments to each other, which I didn’t appreciate.

As a critic, I’m sure I should put my foot down and have a concrete opinion of this text, but I can’t in good faith. It’s—difficult. It’s upsetting. It’s got something to say about women and society. But, I think that Russ makes these arguments better elsewhere, without (what seems to be) the baggage of fiction standing in the way. The ending is certainly an intentional experiment and not a loss of control, but what it has to say to me, as a reader looking back, is that Russ had lost her patience with the novel as a form to make her arguments. It was too unwieldy. She couldn’t speak directly to the reader the way she wanted to, and in fact tried to, breaking down the narrative entirely. It’s an extrapolation on my part, but I suspect it to be true based on this text and where Russ’s career continues down the road.

*

Her next book is a leap from the usual form into something new: a children’s book. That children’s book, Kittatinny: A Tale of Magic (1978), is the next text of Russ’s on the menu.

The entire Reading Joanna Russ series can be found here.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.